Hamilton, a freeflowing Bubble Tea Assistant

Code found here.

Rationale

The Turing Test was developed by Alan Turning in 1950. At its essence, it connects a human, the intergator, with (1) a machine designed to mimic human responses on a text-based platform and (2) another human. After having separate conversations, If the evaluator cannot distinguish the machine apart from the human, the machine is to have passed the Turing Test.

The Lobner Prize is an annual competition awarded to the most human-like program, determined through a series of Turing Tests. For the past 5 years, the prize has been given to Mitsuku, now deemed by many as the world’s best conversational chatbots. Talking to her and discovering her knowledge of specifics was very impressive. Mitsuku was keen to tell me how I could use bricks to build houses, and that no, I should not be eating bricks. I was intrigued by how this all worked, and after talking to Mitsuku some more, I was galvanized to building my chatbot.

Research and Planning

There are three main models to making a chatbot, based on how the chatbot retrieves the information and where it gets the information from. Retrieval based ones have a corpus of dialogue and use machine learning models to finetune responses and interpretation over time while generative chatbots can formulate original responses using neural networks. You may have heard of Microsoft’s Twitterbot, Tay. In 2016, full of comments from trolls, this generative chatbot was tweeting pro-nazi statements and hate speech within 16 hours of its release. I, however, wanted my chatbot to be more achievable. My chatbot would be rule-based, meaning all its dialogue would be predefined and there would be no fancy learning done. However, I wanted there to be a conversation, free-flowing and akin to what you might have with a human.

On came the exploration of my chatbot’s purpose. The chatbot needed to be specific enough so that it could be useful, and on a domain that I could have fun with exploring. Hence, as the proud CEO of Abi’s Bubble Tea House, I needed to make a chatbot that could help customers place bubble tea orders. Surely you’ve seen how long the lines are during peak hours at Coco (during non-Covid19 hours, of course). Excited about what would take place, I began my project.

drinks_menu = {

'strawberry pineapple explosion': 4.30,

'unicorn confetti': 3.75,

'stormy pouf': 3.75,

'original milk tea': 3.50,

'sunshine yogurt': 4.50

}

toppings_menu = {

'tapioca pearls': 0.75,

'grass jelly': 1.5,

'red bean': 0.75,

'whipped cream': 1.00,

}

Approach

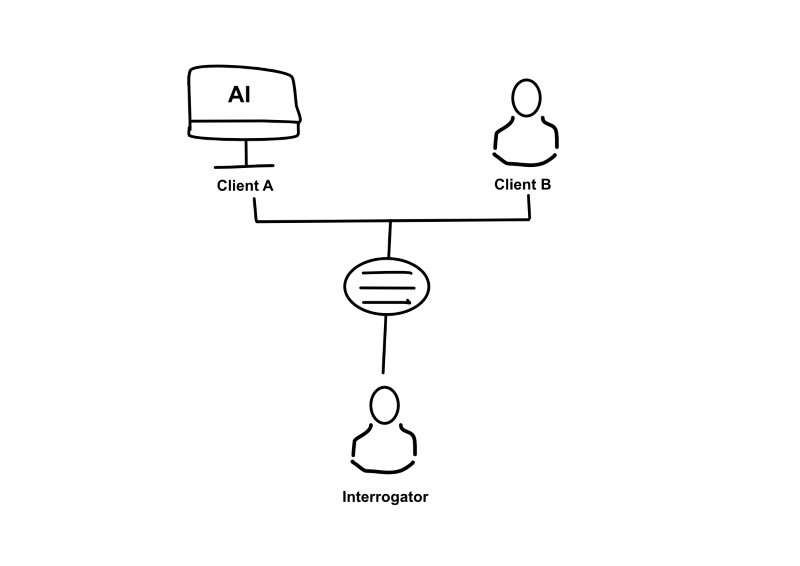

I started by mapping out possible pathways a conversation with Hamilton could go.

Cleaning User Responses

When the user talks to Hamilton, many words can be filtered out. For example, in the context of ordering drinks, just the word “menu” in a sentence could represent “Can I see the menu?” Hence, I needed to clean up each of the user’s responses, autocorrect the words, and also pick out the essential words when needed. To do this, several steps were undertaken:

Tokenization

When a sentence is tokenized, the text is separated into individual pieces called tokens. The piece can be of paragraphs, sentences, or in my case, individual words. This was done using the Natural Language Toolkit (NLTK) library in python. Furthermore, to ensure uniformity, each word was converted to lower case.

Autocorrect

A way to check for text similarity is by the Levenshtein distance of two words. The distance is calculated through the minimum number of insertions, deletions, and substitutions that would need to occur for one word to become another. For example, turning “boat” into “boots” would require one substitution (“a” for “o”) and one insertion (“s”), so the Levenshtein distance would be two.

I supplied a list of keywords that I was looking to autocorrect. These consisted of the most valuable words needed to refer to menu items and drink descriptors.

` keywords = [“strawberry”, “pineapple”, “explosion”, “unicorn”, “confetti”, “stormy”, “pouf”, “original”, “milk”, “tea”, “sunshine”, “yogurt”, “tapioca”, “pearls”, “grass”, “jelly”, “red”, “bean”, “whipped”, “cream”, “ice”, “more”, “less”, “no”, “sugar”, ‘and’, “normal”, “large”, “small”, “medium”] `

Then, all the words the user replied with would be compared to each of the keywords, and any word which has a Levenshtein distance of 1 (this would be so that word would not be incorrectly autocorrected) would be corrected to one of the keywords. A method to calculate this distance was also supplied in the NLTK library.

Stopword Removal

Not all the words the user responds with are critical to their intent. For example, “I would like to order a large bubble tea with less ice” could be stripped down to “large bubble tea less ice”.

Stopword Removal was a supplementary cleaning function (as opposed to autocorrect and tokenization, which was done to all user responses except during user feedback) as not all situations required such an explicit level of cleaning. There are moments where context is necessary, such as when the user wants to order the special vs hear about the special.

With the inputs all cleaned up, it’s time to tackle user intentions.

Understanding User Intentions

Regular Expressions, also known as regex, is a special sequence of characters that describe a pattern that should be matched in a string. This is used in web forms, to ensure the user corrected entered an email, to find keywords. Functions related to regex were from the re library. For example, at the end of Hamilton, when the user is ready to input their address, this code checks the user’s input for a string that matches a postal code:

postal_code = re.findall(r'[a-z]\d[a-z]', postal_code_reply)[0]

Particularly, this regex looks for the first occurrence of a lowercase letter, followed by a digit, then another lowercase letter.

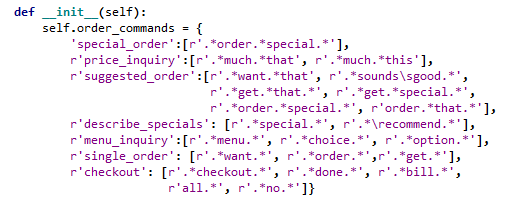

Regex is extremely useful in understanding user intent. We can have a dictionary of all possible intentions the user can have, along with regex that would trigger such intentions. Then, when the user responds, the response loops through all the regex and the one that matches the user’s response is the user’s intention. For Hamilton, this looks like this:

When a regex pattern is found, a function corresponding to that intention is called. If a regex pattern is not found, the user is asked to rephrase their request. If this occurs 3 times, Hamilton advises the user to call the store.

Understand Drink Orders

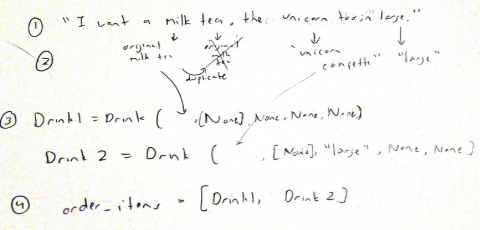

One thing that Hamilton needed to do was to distinguish wish descriptors matched which drink, as a customer might order several drinks in the same string. At first, I thought of using ‘and’ as a way to separate drinks. However, that’s not the only use ‘and’ could have. ‘I want a milk tea and a sunshine yogurt’ is different than ‘I want a milk tea with red beans and tapioca.’ Therefore, to use ‘and’ as a separator of multiple drinks, it would need to recognize that the word before and after “and” were not toppings. This was simple, as I could just identify if both of those keywords were in toppings_menu.keys(). This allowed Hamilton to identify “I want a milk tea and a large stormy pouf” as (“milk tea”), (“large” “stormy pouf”).

However, ‘and’ isn’t the only separator humans use. If a customer mentioned the name of a new drink, this was a clear indicator that they started talking about another drink order. This allowed for the identification of ‘I wish to get unicorn confetti, strawberry pineapple, finally a sunshine yogurt with red beans’ as 3 drinks.

“Strawberry pineapple explosion” is a mouthful to say. I wouldn’t be surprised if people referred to it just as the “explosion”, and Hamilton needed a way to realized that’s what customers meant. Therefore, when the customer names a drink, the word the customer uses loops through all individual tokens in the full drink names. If a word matches a token, then Hamilton recognizes the drink by that full name. If the next word used also refers to the same drink, the word is skipped. This is to prevent a drink like “original milk tea” being detected as 3 separate drinks. This was also done for toppings.

Finally, when people order drinks, they wouldn’t be expected to give any more information than the name and the size in their inital statement. Therefore, after a drink response, Hamilton saves the drinks given and initializes any of the 5 descriptor values (I would expect this to be ice level, sugar level, and toppings) that do not have a value with None. The drinks are placed in a list, order_items, where a method goes through each Drink and asks the user about a particular value.

I was also able to implement a very superficial version of context understanding by saving the last drink that was referenced. For example, if Hamilton mentions the special, special is saved to last_reference, so when the regex picks up the user replied with a phrase containing both ‘want’ ‘that’, the special is added to the order_items list ready to be completed.

Calculating Delivery Time

Originally, I wished to use Google Map’s API for this. However, this was not free, so I resorted to crude, manual calculation. Using the pgeocode library, it allowed me to convert postal code address to longitude and latitude values. I then used the Haversine formula to calculate the spherical distance between the user’s postal code and the Bubble Tea shop, which at this point I decided should be located at 648 Yonge Street, Toronto, Ontario (sorry Coco’s). I then assumed the driver goes at 30km/h and gave the shop an extra 10 minutes as a buffer.

Sentiment Analysis

Sentiment analysis refers to deciphering the emotions associated with a sentence. Normally, this would be done with a Naive Bayes (NB) model in a supervised learning setting. The NB model would take in corpora specific to the text one wished to analyze, with sentiment values preassociated to it. The model would then predict the overall sentiment of novel sentences. However, I did not have this luxury, so I used the VaderSentiment library, with an API for automatic sentiment analysis scores. This was a more authentic implementation to interpret user intention compared to asking the user to input (y or n) or looping through a premade list of affirmatives. This also allowed me to take all parts of the sentence into sentiment consideration.

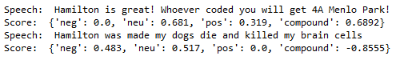

A look at vaderSentiment. The individual scores represent the proportions of tokens that fall into each category:

Sentiment analysis is also used at the end of the order where Hamilton asks the user for feedback. Hamilton adapts his responses to the user’s sentiments.

Conclusion

Language processing and the techniques used for chatbot creation were things I had only a very basic understanding of before doing this project; however, the creation of Hamilton helped me begin to get familiar with these concepts. This was also the first project I did in Python, and the using of OOP concepts and learning syntax were very beneficial.

I don’t think I’m quite done with Hamilton; there is one more thing things I want to do to push the project a bit further, which is the implementation of user suggestions.

Humans are indecisive creatures, and often I resort to a “what do you recommend” after reading a menu several times. Ideally, I would like Hamilton to be able to give the user data-backed suggestions. For example, If the user has a (“Milk Tea”, “Large”}, Hamilton should give the ideal toppings to put on. What I can do is use word embeddings, which are vector representations of words. First, I would need data on combinations of bubble tea orders using real customer orders. Then, using the gensim library and this database of bubble tea combinations, I would then train my word embedding model, where each training piece is 5 words (n-gram, with n=5, representing all 5 descriptors).

All in all, this was one of the most fun projects I had ever done, and I will try my hand at bigger bots in the future, with the next one either generative or retrieval-based. After spending tens of hours on Hamilton, closing the program felt strangely saddening. For the time being, Hamilton lives here, feel free to experiment with it!